- Dimension 1: Acute intoxication and/or withdrawal potential

- Dimension 2: Biomedical conditions and complications

- Dimension 3: Emotional, behavioral, or cognitive conditions and complications

- Dimension 4: Readiness to change

- Dimension 5: Relapse, continued use, or continued problem potential

- Dimension 6: Recovery environment[1]

|

ASAM Criteria Level of Care |

||

Level of Care |

Adult Title |

Description |

0.5 |

Early Intervention | Assessment and education for at-risk individuals who do not meet diagnostic criteria for substance use disorder |

1 |

Outpatient Services | Less than 9 hours of service/week (adults); less than 6 hours/week (adolescents) for recovery or motivational enhancement therapies/strategies |

2.1 |

Intensive Outpatient | 9 or more hours of service/week (adults); 6 or more hours/week (adolescents) to treat multidimensional instability |

2.5 |

Partial Hospitalization | 20 or more hours of service/week for multidimensional instability not requiring 24-hour care |

3.1 |

Clinically Managed Low-Intensity Residential | 24-hour structure with available trained personnel; at least 5 hours of clinical service/week |

3.3 |

Clinically Managed Population-Specific High-Intensity Residential | 24-hour care with trained counselors to stabilize multidimensional imminent danger. Less intense milieu and group treatment for those with cognitive or other impairments unable to use full active milieu or therapeutic community |

3.5 |

Clinically Managed High-Intensity Residential | 24-hour care with trained counselors to stabilize multidimensional imminent danger and prepare for outpatient treatment. Able to tolerate and use full active milieu or therapeutic community |

3.7 |

Medically Monitored Intensive Inpatient | 24-hour nursing care with physician availability for significant problems in Dimensions 1, 2 or 3. Sixteen hour/day counselor ability |

4 |

Intensive Inpatient | Available to engage patient in treatment |

OTP (level 1) |

Opioid Treatment Program (Level 1) | Daily or several times weekly opioid agonist medication and counseling available to maintain multidimensional stability for those with severe opioid use disorder |

| Adapted from Mee-Lee, D. (2013)[8] with permission. See the ASAM Criteria: Treatment Criteria for Addictive, Substance Related-, and Co-Occurring Conditions, for a full description and guidance for the use of criteria. | ||

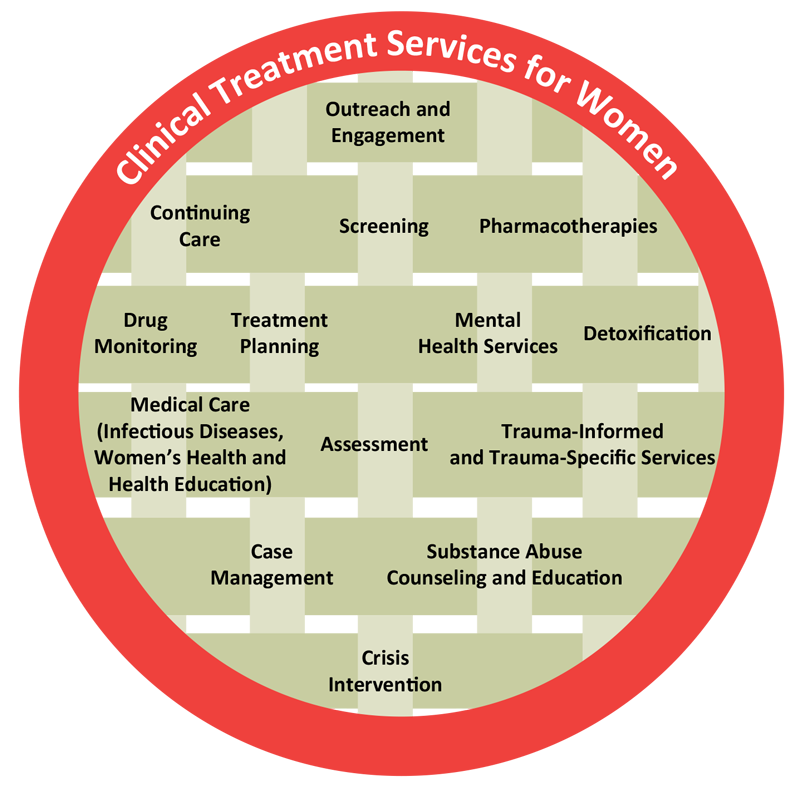

Within the different levels of care listed by ASAM, there are numerous approaches to treatment that may be employed. Several of the treatment approaches most relevant to women struggling with opioid or other substance-use disorders are described in the following sections that are reprinted with permission, from the National Abandoned Infants Assistance Resource Center Fact Sheet “Prenatal Substance Exposure”. (http://aia.berkeley.edu/media/pdf/AIAFactSheet_PrenatalSubExposure_2012.pdf):

[For more information see: Substance Abuse Treatment: Addressing the Specific Needs of Women. A Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series. No. 51. HHS Publication No.(SMA)13-4426. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration, 2009. Or go to: http://www.samhsa.gov/women-children-families]

| b. Residential Substance Abuse TreatmentResidential treatment for women and their children is one method of concurrently addressing the needs of both substance using mothers and their children. These programs have higher retention rates compared to outpatient clinics and long-term positive effects, particularly if they are gender specific and family-focused.[7] Participants in women-specific residential treatment have also been shown to be more likely to participate in continuing care following discharge.[8] Such programs are often geared toward women-specific issues, promoting the parent-child relationship, and addressing the many other problems associated with chemical dependency (e.g., housing, social, psychological, and employment issues). For example, they can involve teaching hands-on parenting skills to substance users which may bring stability into the lives of their at-risk children, including both the newborn and older children.[9] Furthermore, residential treatment programs for pregnant women have been shown to lead to better birth outcomes in terms of infant mortality, premature delivery and low birth weight, as well as improved economic well-being and personal relationships.[10]c. Trauma-informed TreatmentBecause many pregnant substance users also have a history of trauma, treatment is most effective if it is also trauma-informed.[11] Current delivery systems are not yet consistently screening for and addressing trauma in treatment. Further, they tend to be poorly integrated and focus on the client’s immediate safety rather than long-term recovery from the trauma and co-occurring disorders. Recognizing the inadequacy of treatment for women with co-occurring disorders and histories of trauma, SAMHSA identified four core principles to inform best practices with this population [emphasis added]:

1) Organizations and services must be integrated. 2) Settings and services must be trauma-informed. 3) Consumers, survivors or recovering persons must be integrated into the design and provision of services. 4) A comprehensive array of services must be made available.[12]

Implementing these elements may take time, additional staff training and support, and the collaboration of various organizations, but the result will be a service delivery system better equipped to serve women with co-occurring disorders and trauma histories. |

[For more information see: SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. HHS Publication No.(SMA) 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration, 2014. Or go to: http://www.samhsa.gov/nctic]

| d. Treatment for Co-occurring DisordersThe fact that mental illness so often co-occurs with substance use disorders in women also necessitates the development of effective programs that treat both disorders. Several models currently exist to address the treatment of co-occurring disorders in pregnant and parenting women.[13] In the serial model, substance abuse is addressed first after which the client moves on to traditional psychotherapy.[14],[15] However, this model might be ineffective given the high substance abuse relapse rate among addicts and those with severe psychiatric disorders. In the parallel model, treatment for psychological problems and addiction are delivered at the same time but in different milieus. This method allows for close collaboration between agencies, but may still not be coordinated enough for clients with acute mental disorders. The third, integrated model, is recommended for clients with severe or pervasive psychological illness. This treatment model brings together addiction treatment and psychological therapy for an intensely integrated treatment plan. |

| e. Family Treatment Drug CourtFamilies affected by substance use disorders may also benefit from family treatment drug courts (FTDCs) which, unlike standard courts, are tailored to the needs of substance abusing parents.[16] Like adult drug courts, FTDCs include regular court hearings, judicial monitoring, drug testing and treatment, and regular monitoring of performance with predictable rewards and sanctions.[17],[18] However, the primary focus of FTDCs is family reunification, rather than avoidance of jail time, as is the case in adult drug courts.FTDCs offer services addressing the needs of the entire family, which may include older children, multiple parents, grandparents, and other relatives. Services generally are in the form of case management, drug and alcohol assessment and treatment, education, parenting support, and domestic violence services.[16],[17] FTDCs also form partnerships with medical and social service providers in the community to help connect families to the other services they need. A four-year study of FTDCs found that they are more effective in helping substance abusing women complete treatment and reunify with their children than traditional child welfare case processing; FTDC children also spend less time in out-of-home care than children in traditional courts.[16] |

f. The North Carolina Perinatal &Maternal Substance Abuse and the CASAWORKS for Families Residential Initiatives

Introduction to Initiative by Jude Johnson Hostler, LCAS

The North Carolina Perinatal and Maternal Substance Abuse and CASAWORKS for Families Initiatives (Initiatives) represent a nationally recognized state-wide approach to the many social and health challenges associated with family addiction. It is comprised of 28 programs using evidence-based treatment models located in 13 counties across the state. The Initiatives include a robust effort for cross-service area referral so that no pregnant woman or woman with children seeking treatment and who is willing to engage in her own community, or move to another site in the state should her community not have services, need go without treatment. Women with substance use and associated co-morbidities are supported to engage with family-centered, gender-responsive treatment with their children.

Over 20 years of research show that women are motivated to engage with treatment and recovery by concern for their children or pregnancy but that they are often unwilling to seek treatment if it means leaving their children. The NC Initiatives address this by providing family-responsive care. All of the programs in the Initiatives are considered cross-service area, which helps to meet the need of pregnant and parenting women who do not have gender- or family-responsive treatment in their home communities. Through a capacity management system, health care providers, department of social services social workers, and treatment providers can refer women and their children to the services they need anywhere in the state. Women in need of services and their families can also access this system to identify appropriate treatment resources statewide.

Programs provide gender-responsive and family-centered services that include, but are not limited to:

- Evidence-based behavioral health treatment services for pregnant and parenting women

- Referral for and coordination with medical care for women

- Arrangements for treatment and prevention services for children

- Pediatric and developmental care for children

- Job readiness and job coaching are key provisions in our 8 CASAWORK for Families sites which have a primary goal of self-sufficiency

- Parenting education and support

- Case management

- Transportation services

For more information, see http://alcoholdrughelp.org/getting-help/womens-services/

g. Connecting Women to Treatment in North Carolina

The NC Perinatal Substance Use Specialist at the Alcohol Drug Council of North Carolina, provides information and referral to alcohol and drug treatment for pregnant and parenting women. She can be contacted at 1-800-688-4232.

Local Management Entities-Managed Care Organizations (LME-MCO) provide telephone-based screening, triage, and referral to treatment for residents of their catchment areas. To determine which LMC-MCO to call for a county of residence, consult the listing available at: http://www.ncdhhs.gov/mhddsas/lmeonblue.htm

Treatment resources can also be accessed here.