Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome

There are many variables that impact if, how, and when an infant will experience withdrawal symptoms. These include:

- timing of the mother’s most recent intake of opioid

- maternal metabolism

- placental metabolism

- infant metabolism and excretion

- maternal taking of other substances, including cigarettes, cocaine, hypnotics sedatives, and/or barbiturates[1]

Opioid withdrawal in a newborn causes central nervous system excitability or hyperirritability, such as tremors, stiff or rigid muscle tone, and vasomotor signs, as well as gastrointestinal signs, including vomiting and loose stools. The onset of the symptoms varies; however, infants exposed to heroin or other short-acting opioids will typically show symptoms within the first 48–72 hours after birth. Those exposed to methadone or buprenorphine, which are longer acting opioids, will often present symptoms later than 72 hours, but usually within the first 4 days. The severity and duration of the withdrawal symptoms can be influenced by exposure to other substances, including tobacco and barbiturates.[1] Poly-substance use may be more the rule for women with an opioid-use disorder, with two notable exceptions: (a) women who are in long-term recovery and receiving medication-assisted treatment (who become pregnant after beginning treatment), and (b) women whose opioid use was limited to prescribed opioids taken under medical supervision for pain management.

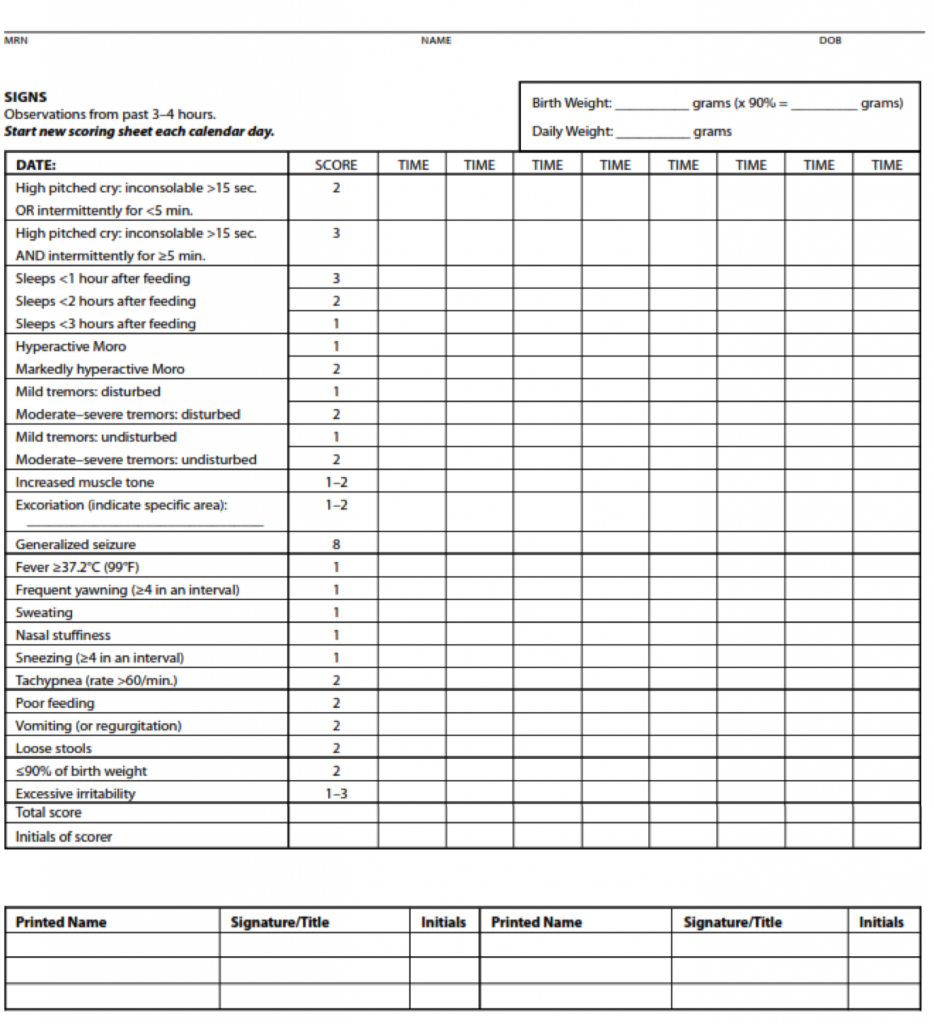

To assess the signs and severity of withdrawal in an infant, practitioners use a standardized scoring system such as the system first developed by Finnegan[2] and later modified by Jansson[3] and others. When this type of standardized scoring tool is used by well-trained healthcare professionals, the instrument enables the practitioner to make an assessment, identify the withdrawal symptoms, document the infant’s withdrawal, and initiate the appropriate treatment regimen, when needed.[4] Increasingly, practitioners are teaching the mothers how to use the scoring tool, allowing the mother to actively participate in her infant’s monitoring. Elevated scores indicate a clinically significant withdrawal, and the infant might be a candidate for pharmacologic treatment.

At times, substance exposure is identified using toxicology screening of the newborn’s urine and meconium (i.e., first stool), especially in cases in which the mother has not been in a substance-use disorder treatment program and has not been forthcoming with the medical team. Urine testing (i.e., urinalysis) generally reflects substance exposure within the past several days, depending upon the substance. Results of these tests are rapidly available; however, urinalysis produces a high rate of false–negative results due to the rapid clearance of most drugs from the newborn’s system and the difficulty in obtaining the volume of urine need for testing from an infant in the first day of life. Meconium toxicology screens can reveal substance exposure during the previous several months of pregnancy. However, obtaining the meconium test results may take several days, by which time the mother and infant are likely to have been discharged. Umbilical cord tissue is another diagnostic for infant toxicology. One advantage of umbilical cord tissue sampling is that the cord is always available, where meconium can be missed due to excretion in utero. The results are available faster, which allows for better informed treatment and going home decisions. The test requires six inches of umbilical cord tissue and provides a longer histology of prenatal drug exposure, but may also detect medications used in labor and delivery.

Opioid withdrawal symptoms can mirror symptoms of other conditions in a newborn, such as infections, very low blood sugar, very low blood calcium, low thyroid hormone, and problems with the brain (e.g., cerebral palsy).[1]

Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome (NAS) Scoring and Management

The Finnegan Neonatal Abstinence Scoring System is the most commonly used scoring tool, although the original tool has been modified frequently.[5] Below is a modified Finnegan NAS Scoring form developed by Jansson, Velez, and Harrow[3] and further modified by the Fletcher Allan Hospital of Vermont. See Appendix A for an explanation of the scoring.

Treatment of NAS

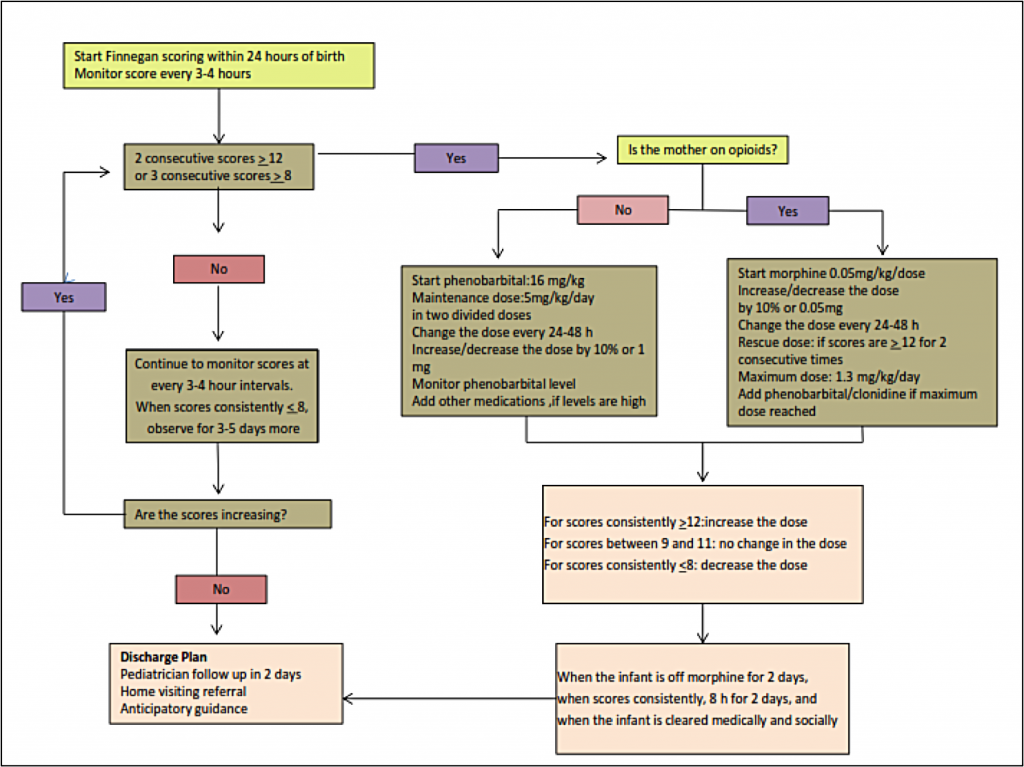

Approximately 50% –75% of infants exposed to opioids before birth will require pharmacologic treatment for opioid withdrawal. At the delivery of a known opioid-dependent woman, naloxone should be avoided in resuscitation of the infant because the drug can precipitate seizures.

Initial treatment of infants showing signs of withdrawal is focused on supportive care. It is important that this treatment approach is standardized within care settings. Supportive care can include creating a low-stimulation environment that is dark and quiet, swaddling the infant to inhibit self-stimulation, and providing frequent/on-demand feedings to reduce infant stress.[1] Other beneficial strategies include encouraging skin-to-skin contact for comfort and promotion of the infant’s attachment to the mother/caregiver, as well as other comforting techniques such as rocking or swaying the infant.[7] Providing frequent feedings helps to address the infant’s hydration level, although many infants will require intravenous fluids to maintain adequate hydration. Frequent feedings also address the high energy expenditures associated with withdrawal (thus a need for increased calorie intake) and a symptom of withdrawal where infants engage in excessive sucking but with poor feeding.[8] Teaching these techniques to families and caregivers, including careful, detailed demonstrations, is an important factor in the success of the supportive care approach.

Breastfeeding is encouraged in cases when the mother is receiving medication-assisted treatment and has no contraindications, such as positive HIV status. However, the infant’s weight must be carefully monitored to ensure that the infant continues to gain weight. Breastfeeding has been associated with specific benefits for opioid-exposed infants, including less severe NAS and reduced need for pharmacologic intervention. [9],[10],[11]

Pharmacologic therapy is indicated for infants who have greater severity of symptoms of exposure and in cases in which the infant has severe vomiting, diarrhea, or excessive weight loss. Infants may be treated with a variety of medications including short-acting opioids (e.g., morphine sulfate) or long-acting opioids (e.g., methadone).[1] The majority of physicians in the United States use morphine or methadone in the treatment of NAS:[4]

…each nursery should develop and adhere to a standardized plan for the evaluation and comprehensive treatment of infants at risk for or showing signs of withdrawal.[1]

The Perinatal Quality Collaborative of North Carolina (PQCNC) began a quality improvement project in 2014 for NAS. Across the state, 29 hospitals have enrolled in the quality improvement effort. The project’s primary aim is to help hospitals provide a standardized, multidisciplinary approach to the identification, evaluation, treatment, and discharge of infants who have experienced NAS. This protocol includes the infants’ families. Each hospital team has engaged in an intensive process of Plan, Do, Study, Act, to determine the most effective standardized practices for their respective setting. The early, important outcomes of the PQCNC effort to standardize NAS protocols have included reducing the length of stay in the hospital for the infant and family. For more information: http://www.pqcnc.org/node/13348

Location of Care Is Specific to the Hospital

The majority of hospitals that monitor infants for signs and symptoms of withdrawal conduct such assessment on the following units:

- Mother/Baby

- Newborn Nursery

- Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU)

- Special Care Nursery or Level II nursery

- Pediatric ward

If a delivery hospital does not have a NICU or is otherwise not equipped to provide pharmacologic treatment to the infant, the infant should be transferred to a hospital that is able to provide appropriate treatment for the infant.

Discharge Considerations

A new mother undergoes significant stress during the post-partum period, and this stress may be heightened for a woman who has an opioid-use disorder or is in recovery from an opioid-use disorder. Therefore, it is essential for the well-being of the mother and infant that a comprehensive discharge plan is developed to address critical factors, including maternal substance-use disorder treatment, a safe living environment, and parenting and community support. In addition, if not already involved, the mother should receive referrals to Care Coordination for Children (CC4C) and the local home-visiting program. See “Services for Women with Opioid Exposed Pregnancies in North Carolina” referral agencies.

Anticipatory Guidance

Caregivers of infants and children exposed to substances (e.g., opioids, alcohol) during their fetal development, will need to be aware of developmental milestones and track which milestones the child has achieved and those that may be lagging behind. Making the child’s pediatrician aware of all exposures will assist him or her in tracking the child’s development, including behavioral development. Referrals to specialists, including developmental-behavioral pediatricians, can help identify and assess other areas in which the child may need support. Areas of focus for the pediatrician with the infant will include:

- motor deficits and cognitive delays;

- hyperactivity, impulsivity, and attention-deficit in preschool-aged children, and in addition to school absence, school failure, and other behavioral problems in school-aged children; and

- growth and nutritional benchmarks to identify failure to thrive and short stature.[6]

Caregivers of infants should give special attention to safe sleep practices (e.g., placing infant on back, removing toys, blankets, and pillows from cribs) and the elevated risk of Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) for a substance exposed infant, should be emphasized.[12],[13],[14]

Environmental factors also have an impact on child development. Thus, an important area of focus is identifying the available supports and linking caregivers with those supports to promote a stable, violence free, nurturing home environment. The earlier a need is identified and supports are offered, the better the long-term outcomes for the child.[15]

The complexity and challenging nature of the home atmosphere should never be underestimated in these situations. The importance of an optimal home environment for the global development of these children should be emphasized to all parents.[6]