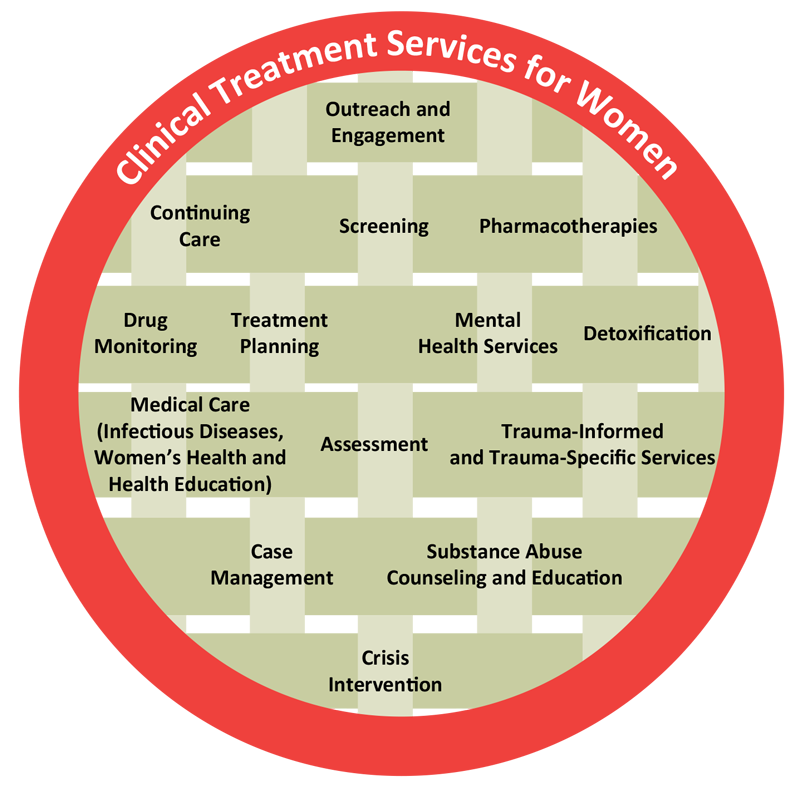

| a. Gender-Specific Treatment for Women Traditionally, substance abuse treatment programming has been geared toward males without regard for the specific needs of women. Yet, increased research on gender differences in substance use disorders highlights the importance of gender-specific programs.[1] A recent survey showed that substance abuse treatment facilities with special programs for women generally offer individual, group, and family counseling; discharge planning; social services assistance; child care; domestic violence services; and accommodation for children.[2] Many substance using women are in relationships with drug-abusing, and often violent, partners or spouses and they are more likely than men to consider this relationship to be the cause of their drug abuse.[1] Research suggests that the benefits from group therapy are better maintained when women participate in women-only groups compared to mixed-gender groups, perhaps because there are particular issues (e.g., physical or sexual abuse) that many clients feel more comfortable sharing only with other women.[3] Pregnancy-specific treatment programs have also been developed to address concerns specific to this population (e.g., health and nutrition during pregnancy) and provide pregnancy support that more traditional women’s programs might not offer. Research indicates that women in pregnancy-specific programs are more likely to complete treatment compared to those in traditional treatment groups.[4] Providers who work with substance using women consistently point to stable, nurturing relationships with peer workers, professional case managers, or others as key to supporting women. Building upon this, the recovery coach model is emerging as a promising approach to serving substance using pregnant women.[5] A recovery coach is a paraprofessional who assists parents in obtaining needed benefits, coordinates child welfare and substance abuse treatment staff, and connects the family with treatment providers. Coaches often participate in joint home visits with child welfare workers or substance abuse treatment staff, but are independent from these agencies, ensuring that their focus remains on the family. Evaluations have found that the use of recovery coaches significantly decreases the risk of substance exposure at birth.[3] |

[For more information see: Substance Abuse Treatment: Addressing the Specific Needs of Women. A Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series. No. 51. HHS Publication No.(SMA)13-4426. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration, 2009. Or go to: http://www.samhsa.gov/women-children-families]

| b. Residential Substance Abuse Treatment Residential treatment for women and their children is one method of concurrently addressing the needs of both substance using mothers and their children. These programs have higher retention rates compared to outpatient clinics and long-term positive effects, particularly if they are gender specific and family-focused.[6] Participants in women-specific residential treatment have also been shown to be more likely to participate in continuing care following discharge.[7] Such programs are often geared toward women-specific issues, promoting the parent-child relationship, and addressing the many other problems associated with chemical dependency (e.g., housing, social, psychological, and employment issues). For example, they can involve teaching hands-on parenting skills to substance users which may bring stability into the lives of their at-risk children, including both the newborn and older children.[8] Furthermore, residential treatment programs for pregnant women have been shown to lead to better birth outcomes in terms of infant mortality, premature delivery and low birth weight, as well as improved economic well-being and personal relationships.[9]c. Trauma-informed Treatment Because many pregnant substance users also have a history of trauma, treatment is most effective if it is also trauma-informed.[10] Current delivery systems are not yet consistently screening for and addressing trauma in treatment. Further, they tend to be poorly integrated and focus on the client’s immediate safety rather than long-term recovery from the trauma and co-occurring disorders. Recognizing the inadequacy of treatment for women with co-occurring disorders and histories of trauma, SAMHSA identified four core principles to inform best practices with this population [emphasis added]: 1) Organizations and services must be integrated. 2) Settings and services must be trauma-informed. 3) Consumers, survivors or recovering persons must be integrated into the design and provision of services. 4) A comprehensive array of services must be made available.[11] Implementing these elements may take time, additional staff training and support, and the collaboration of various organizations, but the result will be a service delivery system better equipped to serve women with co-occurring disorders and trauma histories. |

[For more information see: SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. HHS Publication No.(SMA) 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration, 2014. Or go to: http://www.samhsa.gov/nctic]

| d. Treatment for Co-occurring Disorders The fact that mental illness so often co-occurs with substance use disorders in women also necessitates the development of effective programs that treat both disorders. Several models currently exist to address the treatment of co-occurring disorders in pregnant and parenting women.[12] In the serial model, substance abuse is addressed first after which the client moves on to traditional psychotherapy.[13],[14] However, this model might be ineffective given the high substance abuse relapse rate among addicts and those with severe psychiatric disorders. In the parallel model, treatment for psychological problems and addiction are delivered at the same time but in different milieus. This method allows for close collaboration between agencies, but may still not be coordinated enough for clients with acute mental disorders. The third, integrated model, is recommended for clients with severe or pervasive psychological illness. This treatment model brings together addiction treatment and psychological therapy for an intensely integrated treatment plan. |

| e. Family Treatment Drug Court Families affected by substance use disorders may also benefit from family treatment drug courts (FTDCs) which, unlike standard courts, are tailored to the needs of substance abusing parents.[15] Like adult drug courts, FTDCs include regular court hearings, judicial monitoring, drug testing and treatment, and regular monitoring of performance with predictable rewards and sanctions.[16],[17] However, the primary focus of FTDCs is family reunification, rather than avoidance of jail time, as is the case in adult drug courts.FTDCs offer services addressing the needs of the entire family, which may include older children, multiple parents, grandparents, and other relatives. Services generally are in the form of case management, drug and alcohol assessment and treatment, education, parenting support, and domestic violence services.[15],[16][16] FTDCs also form partnerships with medical and social service providers in the community to help connect families to the other services they need. A four-year study of FTDCs found that they are more effective in helping substance abusing women complete treatment and reunify with their children than traditional child welfare case processing; FTDC children also spend less time in out-of-home care than children in traditional courts.[15] |